Drawing Exercise: Everything is Related

Here Painting a Head tutor, Robert Dukes discusses the challenges of relating the model to their surroundings and suggests an exercise to help students consider how to place figures in relation to others.

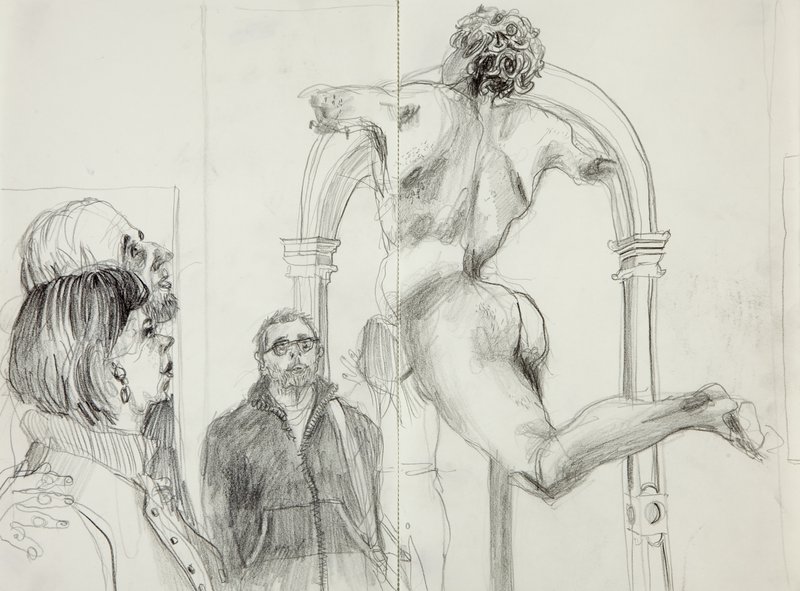

Drawing by Rebecca Harper, Bronze, 2013

One of the biggest challenges in teaching life drawing is trying to encourage students to relate the model to their surroundings- and also to the sheet of paper they’re working on. What usually happens if you leave students to their own devices is a set of drawings of an isolated life model floating in a void; no sense of scale, no sense of how far the model is from the person who drew them, and no sense of the space within the room. No sense, in short, of ‘being there’.

Just as we never see colours in isolation- but in relation to other colours- so we only see objects in relation to the whole- the ‘whole’ being whatever is in our line of sight.

The author of “Cézanne’s Composition” Erle Loran, wrote of “the invariable experience I have with new students in the life class who come with a background of conventional art-academy training in life drawing. When the students are told to organise the entire space, the human figure and its surroundings, to relate it to the format[ i.e. the size and shape of the surface being drawn on], to the picture plane, the first results are usually a total loss of the slick finish in the figure drawing and a general clumsiness that belies the previous training.”

When this collapse of facility happens, it can be very unnerving. In fact, it’s a good thing! It means you’re learning, and learning so intensely there is no room for slickness or polish. If you consider the space and continue your drawing across the entire sheet of paper the whole sheet becomes animated and the lines going to the edge imply a whole world beyond that edge.

Having said all that, almost all life drawings are of a single model. The exercise I want to suggest for you today is to make drawings from the art of the past and specifically to draw at least two figures in relation to each other. You don’t have to draw the whole painting but oddly enough you may find that helps.

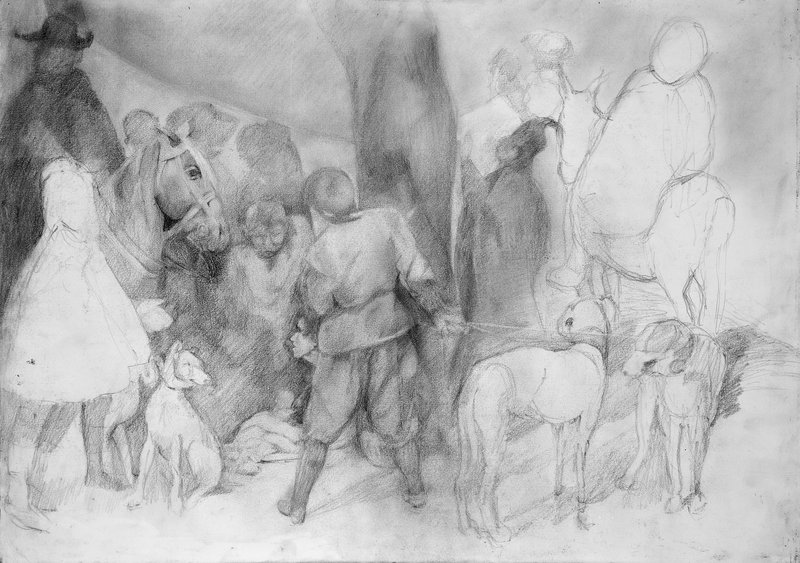

Drawing by Constanza Dessain, After Velazquez's Boar Hunt, 2012

Seeing as you are probably going to be drawing from a computer screen the drawing doesn’t have to be big, so I’d suggest A4 paper and a pencil and eraser.

Suggestions: (all National Gallery paintings; can be accessed on their website)

Degas Combing the hair. NG4865 – Notice how the two women’s arms form a kind of snaking ‘figure 8’

Seurat Bathers NG3908 – Investigate how the figures fill the space and relate to the whole design as flat shapes.

Renoir Umbrellas NG3268 – Is there any space between the figures? And if so, how is it articulated?

Tip 1

Draw the figures concurrently rather than drawing one figure first then adding another one. It could be as simple a decision as “I’ll only make three marks for this figure before making the same amount of marks for the other figure”. Back and forth. If you’re drawing multiple figures think of ‘pass the parcel’. Or spinning plates…

Tip 2

Draw the shapes between the figures(the so-called ‘negative shapes’). You could even do this first. You could even make a drawing consisting of nothing but ‘negative shapes’ and see if the figures magically appear on the paper. The Seurat Bathers would be a good example to try out this exercise.

After you’ve made your drawing of more than one figure, look up some drawings of great art by Cézanne and Leon Kossoff (they both made tremendous drawings from Rubens, for instance). What may have previously seemed like wilfully clumsy or childish scribbles will hopefully be revealed to be some of the most sensitive and precise- ‘precise’ meaning a sense of ‘being there’ – drawings made in the last two centuries.

Drawing by Meg Buick, After Poussin, 2013

In conclusion, being in lockdown has made me more than ever aware of how we are all connected. Drawing your sense of ‘the whole’ in whatever form that takes- may help you feel more connected to your own work, and indeed the world.

References

1 Erle Loran, Cezanne’s Composition, University of California Press. ISBN 0520-05498

2 National Gallery website